Why we shouldn’t correct every error

How many of your students’ errors do you correct when they hand in the first draft of a writing assignment? Everything? First percent of all errors? Twenty percent? Much of the research on this subject says that we shouldn’t correct as much as we think. Why?

- It’s very time consuming to find and mark every error on a student’s paper.

- Pointing out too many errors can lower the motivation of students.

- Most students have a hard time focusing on and processing corrections if there are too many of them.

- Students may mindlessly copy your corrections into their final draft if you’ve shown them exactly how to correct each error, and receive little learning benefit. They’ll simply repeat the errors the next time.

- If you’re giving corrections on the final draft of an assignment, some students will check the grade you’ve given them, then stuff the paper into their bag (or the trash can!)

So, what should we correct?

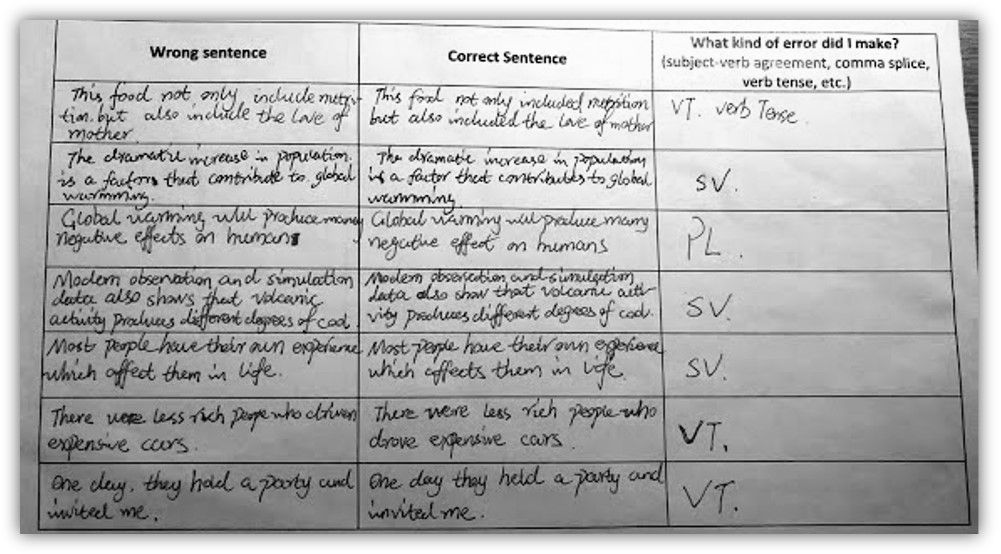

In Teaching ESL Composition (2005), Ferris & Hedgcock point out the difference between correcting errors versus correcting style. When you give corrections to student writing, consider asking yourself these 3 questions to check if they’re going to be useful to students:

1. Am I correcting grammar?

If so, is the student at a level where they’ll understand this grammar and should be expected to use it? (i.e. Don’t point out that they should use the subjunctive if the student is a beginner.)

2. Am I trying to make it clearer to a native speaker reader?

If you’re telling the student to omit confusing or unnecessary words, this could definitely be useful. However, telling them to change their wording using advanced vocabulary they may not know would be less than effective.

3. Am I just giving the student a vague suggestion to make a sentence “more detailed,” “more descriptive,” “more impressive,” etc.? Advanced ELLs and native speakers could benefit from this type of feedback, but it may not be useful for a lower-level students, as they do not have the necessary vocabulary or language knowledge to “add detail,” etc.) In place of his more general feedback, it can help to be specific and explicit. Here are 3 strategies, with examples:

- Give specific number requirements for adding words:

- Student writing: I went to a small school.

- Feedback: “Add 1-2 more adjectives to describe the school.”

2. To help students add detail, use Wh-words to ask specific questions:

- Student writing: The food was very good.

- Feedback: “Why was it good? What did it taste like?”

3. Give an example of what you’d like the student to add:

- Student writing: My friend was very angry.

- Feedback: “Make a comparison/analogy. Was your friend’s head on fire?”

At first, it can be jarring to ignore errors in student writing and not correct many of them. However, it also become liberating for both teacher and student when feedback is focused on a few types of errors, since it saves the teacher’s time and helps students understand and revise their own writing.