What research tells us about written corrective feedback (WCF)

Is written corrective feedback even helpful?

In short, yes; it’s been strongly suggested by research that giving feedback to students on their writing can help them avoid errors in the future, especially for beginners and only if the feedback is given carefully. Wahlström (2014) and Zeleki (2018) give excellent reviews of the research in the area, including longitudinal studies suggesting that students’ improvements can carry over to future pieces of writing. Diane Ferris is another big name in research here, and I’m also a fan of Dr. Conti’s article on his The Language Gym blog, which makes the case for training students in metacognitive and error-avoidance strategies.

Do the improvements last?

However, it’s generally agreed that more studies are needed to support the idea that students’ improvements are lasting, rather than just temporary while the feedback is fresh in their minds. Many studies, for example, show that students improve their writing between their first and final drafts of essays with written corrective feedback (WCF) from the teacher. Well of course they do! But the question is, do their corrections today help them avoid these errors in their writing a year from now? That’s where the need for longitudinal studies comes in.

Although there still remains a need for research in this area, at this point it seems safe to reject Truscott’s (1996) controversial idea that written corrective feedback (WCF) is completely useless and even harmful. Now that we can say with some confidence that WCF can be worthwhile if applied correctly, let’s take a look at how to do so!

Types of errors:

First, it’s useful to classify errors into types so we can focus our feedback. In Learner English, Bernard Smith and Michael Swan (1987) provide us with a nice way of classifying errors into two groups:

- Local errors – These are “small” issues that cause minor annoyance, or may jar the reader slightly and slow down reading speed, but do not interfere with meaning.

Examples: articles (often, but not always), subject-verb agreement

- I have two dog. (We know the student means 2 dogs; the plural “s” is redundant.)

- The leader of our group was create a plan to win the competition. (We know the student meant past tense here.)

2. Global errors – These errors obscure the meaning of a sentence. Thus, we should prioritize correction of these errors.

Examples: articles (sometimes), verb tense, plural, word choice (often)

- I am a shameful person. –> I am a humble person. (Word choice strongly affects meaning!)

- A teacher helped me. –> The teacher helped me. [a specific teacher mentioned prior]

Basically, we’ll get more “bang for our buck” if we help students correct global errors, since they heavily affect meaning. But correcting local errors is also useful if we are training students to leave a professional impression and not “jar the reader,” as with business English.

If you want to find out more about which errors affect the impression of the reader, there are interesting studies on “error gravity;” that is, which errors are more serious than others in creating a negative impression on readers. A nice review of error gravity research (prior to 1995) is Roberts & Rifkin (1995) Some studies on error gravity are Lugwig (1982), Kobayashi (1992), Endley (2016), and Ilin (2017). Wendy Swyt also has a nice chart that ranks the seriousness of errors into an “error hierarchy” here.

How and when to give feedback:

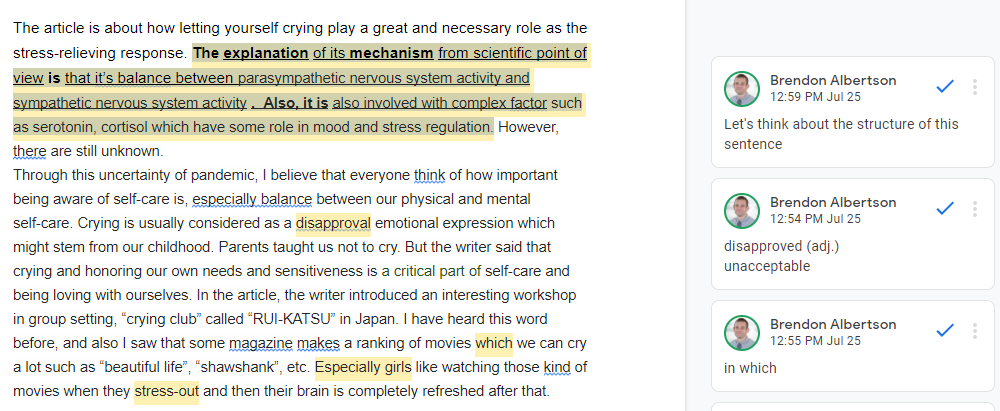

Remember we’re giving feedback to help students learn, not proofreading their papers. Don’t fall into the “proofreading gap!” The golden rule: if they can correct the error themselves, don’t do it for them. This encourages students to become self-editors. There are many ways to mark students’ papers, and it’s important to think about and adjust the explicitness, or directness, of our feedback. (Should we give away the answer? Just a hint? If so, how much of a hint?)

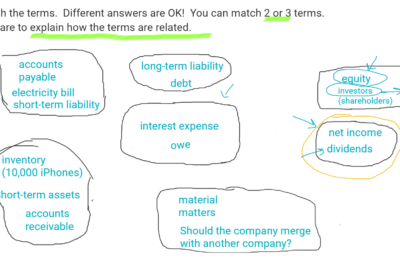

Here’s an example of four “levels” of written feedback we might consider, based on how direct they are:

Level 1: Make a checkmark to indicate there’s an error on a particular line in the student’s paper.

Level 2: Circle word(s) to show the more precise location of the error (but don’t show them the type of error).

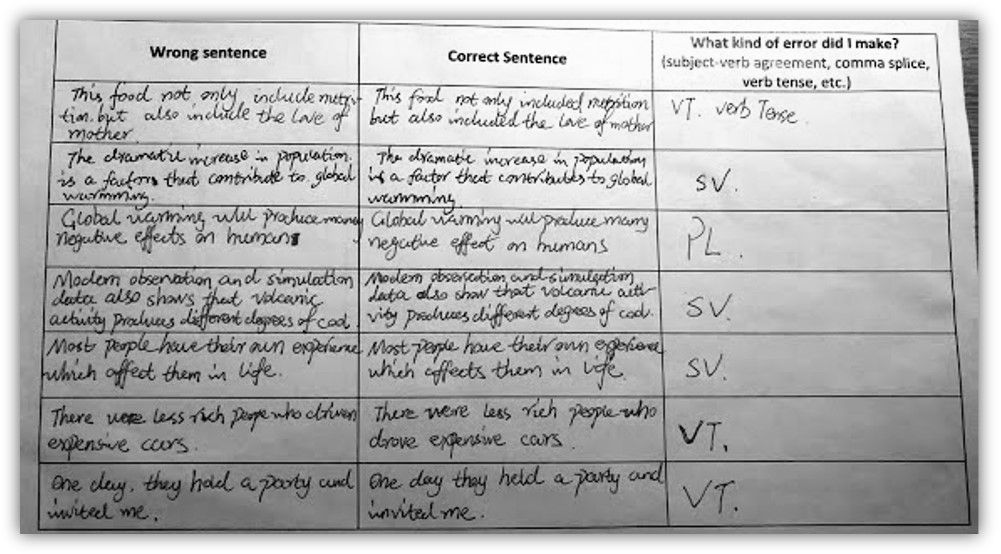

Level 3: Circle the location and use a correction code to show the type of error (as long as you’ve taught the appropriate correction code and students know what it means). Using too many different error codes can be confusing to students, so choose just a few from the list according to which errors you encounter most frequently.

Level 4: Explicit correction (circle the error and write in the correction; i.e. correct it for them)

Obviously, the higher the “level,” the less work the student must do to correct the error. With Level 1, we’re not even showing them the exact location of the error, much less the type, and with Level 4, we’re giving away the “answer” entirely. Again, only give them what they need to self-correct. They may only need a reminder to use the plural, for example.

How direct should we make our feedback?

It depends on how much assistance you think your students need to be able to correct the error on their own. Ferris (2006) makes a nice distinction between errors that are “treatable” (students can correct on their own) and “untreatable” (there’s no way for the student to know how to correct – think word choice or advanced grammar structures they haven’t learned yet). Here are some key points to consider when thinking how to give feedback:

- Treatable errors: give indirect feedback. If it’s an error in grammar or spelling that follows a concrete rule the student should know, the error is “treatable” and so the feedback should be indirect. These include rules like subject-verb agreement, count/non-count nouns, participial adjectives (excited vs. exciting), and simple past vs. simple present tense.

- Example: if a beginner student makes an error with subject-verb agreement although you’ve taught a few lessons on this and are confident they should know it, you might simply circle the subject and verb (and perhaps write “SV” to be a little more direct). The student will hopefully be able to self-correct in this case.

- Untreatable errors: give direct feedback (with choices if possible). For example, an error in word choice is often impossible for a student to self-correct, as the student may not know the nuances of the correct word to use. If a student writes “trusting” when she means “trustworthy,” she can’t correct the error if she doesn’t know the word trustworthy. In this case, we need to either reformulate, or reword, the student’s writing, or give her a few options for alternate words to use. For example, we might write “trustworthy,” “honest,” “sincere,” etc. The student could look up these words and determine which one they feel best fits the context. In this way, the student still has some agency in fixing her own writing – we gave her corrections, but allowed her to choose which one she felt most appropriate.

The importance of knowing your students

Myers (2003) mentions that we should be careful because what seems obvious and self-correctable to us may not be to the student. Thus, it’s important to be familiar your students’ abilities. How can we get familiar? Reserve some time in class for them to study your corrections and revise their writing accordingly. While they do this, you can observe them to see what they know and don’t know, and which questions they may have. Then, you’ll be able to cater your feedback to their abilities, and even differentiate how you give feedback between students.