In this post, I summarize several feelings of loneliness and isolation I’ve felt upon shifting my 13-year career in TESOL from teaching international students and overseas, to teaching in a U.S. public high school.

What’s TESOL? So what do you do again?

This is the question I expected I’d get when I entered my new classroom and saw “TESOL” on the door. Not “ESL,” or “English Language Development,” but the acronym that refers to our field. This was a hint that perhaps most of my new colleagues, including the admin, really didn’t knew what the acronym stood for or what this class really was all about. I was the only teacher on the floor with my own classroom who was not a “content” teacher. Instead, I teach a language, including its vocabulary, grammar, register, and skills for communicating in that language.

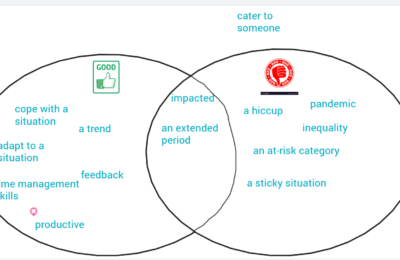

There was no one to bounce TESOL pedagogy ideas off or share materials with. Most PD sessions did not apply to me. No one spoke my lingo, or knew terms like i+1, cloze, or collocation. And what seemed like obvious best practices to me (student talk time, direct vocab instruction, group work, role plays, jigsaw reading, culturally-responsive pedagogy) were seen as somewhat “progressive” teaching strategies brought in from an instructional coach.

I was told at a PD session for the TESOL teachers in our district that we are the most highly trained staff in pedagogy, given the nature of our field. Other teachers might have focused on content in their training, but we focused on how to teach. We were encouraged to be trainers for our colleagues and to build capacity for excellent teaching. While this made complete sense, I felt strange at my role show shifting to a teacher trainer. I, the new teacher, was supposed to train the 25-year veteran science teacher in how to teach better? These colleagues were a far cry from the recent college graduates who knew nothing about ELT but were a pleasure to work with in my TEFL Certificate training class. My current colleagues are wonderful, but to think that training them would be without friction would be erroneous.

English was cool to my Japanese students, but…

Another source of loneliness for the American public TESOL teachers for me was the reception I got from students. It’s often expressed that English teachers can cultivate an inflated sense of expertise and self worth due to their privilege as an English speaker. Students in Japan think the gaijin teacher from the USA is cool, can teach them slang, can help them understand English pop song lyrics, can chat with them about their favorite Disney movies, and in general be a beacon for cool, western stereotypes.

Intrinsic motivation to learn English also comes a bit more naturally in the world of TEFL or international students who come to the US to learn English, but not in public school ESL, where most kids already speak English, are not enamored with Anglo culture, and are required to learn academic English rather than more “fun” language like slang or colloquialisms. Learning academic English can be even more boring to students when they don’t plan to go to college, can’t see the connection with their other classes, or don’t care much about their grades.

Many of the ELLs in the U.S. are Long-term English language learners (LTELs), a demographic for whom there’s only recently been much research, but who have long internalized feelings of being poor students and have a low graduation rate. Effective, early language intervention didn’t happen for them, so their academic language proficiency is not as high.

However, it’s really hard to explain this to students without making them feel dumb or bad about themselves. I’m often told by my American public school MLLs that our ELD class is a “SPED” class they were placed into because they’re “stupid,” which I try to combat by teaching a whole unit on celebrating the benefits of being multilingual at the start of the year.

This is a complete contrast to what I’d experienced with my “English as a foreign language” students. Here in the U.S., there’s no mystique, no “cool” exotic culture to be found in the language, no slang to learn (my students now teach me Gen-Z slang instead), and of course they already know (and detest) many English pop songs. Justin Beiber is not cool here. Disney movies are lame. It’s the plight of the American suburban teenager, and it applies to even our Dominican immigrant students.