Summary:

Textbooks often present gerund and infinitive units by teaching the concept, then asking students to memorize charts showing which verbs are followed by gerunds and which by infinitives. This post questions whether this process is effective, and proposes an alternative way of teaching this grammar.

The gerund-infinitive concept should be taught briefly, then students encouraged create their own charts to keep track of which verbs go with gerunds, infinitives, or both. Similar to a vocabulary notebook or error log, they then add verbs to the chart gradually throughout their studies. In this way, the “gerund or infinitive?” variable becomes simply one more piece of information to memorize when learning a new verb, much like part of speech, syllable stress, or common collocations. These are often key parts of a vocabulary notebook entry, so “infinitive or gerund” could be one more part.

I once taught at a language school specializing in English for Academic Purposes. It prepared students for college by letting them pass all of our 12 levels in lieu of taking the TOEFL test. This was an alternate route that many students preferred, as it was faster in most cases. Students could improve their communicative ability while simultaneously preparing for college, without the monotony and rote memorization that often accompanies TOEFL preparation. So basically, this place was trying to prepare students from the beginning proficiency (Level 1) to college-ready proficiency (Level 12) in just a year. Seem crazy? Maybe it was.

Here’s where the grammar part comes in. I taught an intermediate class several times, in which gerunds and infinitives were introduced. Our school’s proprietary textbook did this by introducing gerunds and infinitives in context (a conversation), then having the teacher explain the concept and drill gerunds and infinitives through games and activities. Sounds OK, right?

The problem: Don’t try to teach grammar and vocabulary at once!

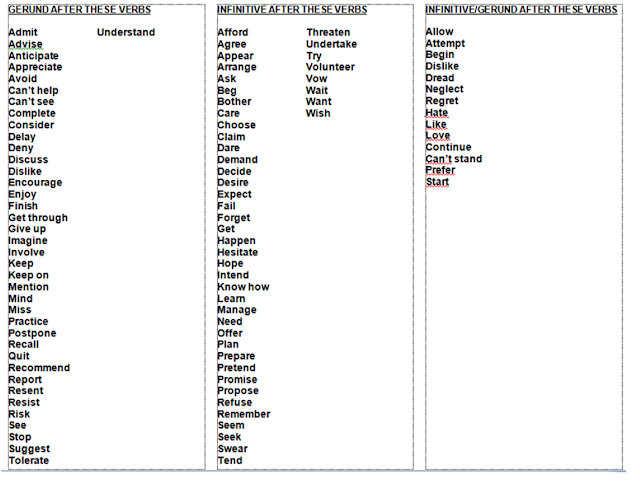

Here’s what I believe to be the problem: an enormous chart with 50 or so verbs was presented, sorted into columns of those that go with a gerund, infinitive, or both (which sometimes changes the meaning, as in stop talking vs. stop to talk.) About 60% of these verbs were new to students, including words like advise and hesitate, and it was the teacher’s job to get students to know:

- the meaning and usage of each verb, and

- whether the verb was followed by a gerund or infinitive.

A large, frightening list of verbs, many of which low-intermediate students likely have never seen before.

So now it’s both a vocabulary and a grammar lesson. The thing was, these verbs were presented in a cold, sterile chart (see above), and no context was provided. Not to mention most of the verbs were quite advances for the intermediate level, and students were not yet in any position to be using some of these verbs. The verbs didn’t belong to any particular theme (jobs, environment, business, etc.). Were teachers thus assumed to be responsible for making themes and contexts and interesting lessons involving these verbs so as to solidify them in students’ minds? Or could a giant stack of flashcards for each student, followed by a test (and encouraging rote memorization) work instead? Neither is a good option.

A possible solution: Just only more piece in your vocab notebook entry!

Students need to know the gerund-infinitive concept, not learn all the possible verbs at once. Instead of assigning dozens of new verbs to study, use verbs that students already know to highlight the gerund-infinitive distinction. Do a few practice exercises with these verbs, perhaps including a few new verbs, and they should have understood the concept.

Next, students should be encouraged create their own charts to keep track of which verbs go with gerunds, infinitives, or both. Similar to a vocabulary notebook or error log, they then add verbs to the chart gradually throughout their studies. In this way, the “gerund or infinitive?” variable becomes simply one more piece of information to memorize when learning a new verb, much like part of speech, syllable stress, or common collocations. These are often key parts of a vocabulary notebook entry, so “infinitive or gerund” could be one more part.

“But wait!” teachers might say. What about all the other verbs the students don’t know? How can they possibly be ready to move on when there are so many more verbs that need to be sorted into these gerund/infinitive categories? The fact is, there are hundreds more. But should you introduce these allin your world-famous gerund-infinitive unit? Of course not. The truth is, after the concept is introduced, students now have it in their heads that when they encounter a new verb, there’s one more variable they must remember about it: whether it goes with a gerund, infinitive, both, or none at all. Students already do this when they encounter a new word. Remember the old saying? “You need to know many things about a word, not just its definition, etc.” Students who make good vocabulary notebooks (and teachers who introduce new vocabulary well) include with every new word the part of speech, collocations, pronunciation, stress, transitivity and irregularity (for verbs), and count/noncount status (for nouns). The gerund/infinitive variable is just one more to enter into their vocabulary notebooks, and one more variable that all teachers who are teaching “gerund/infinitive-aware” students should account for.

This concept is nothing new. When we teach simple past to beginners, we don’t make students memorize lengthy columns of all the regular and irregular verbs. We shown them the concept, and they gradually accumulate verbs until they can handle a large chart in the back of a textbook as an intermediate students. But the point is, students will never know which verbs are regular or irregular for all verbs. They learn them as they come up throughout the course of their English studies, and throughout the course of their life, once they’re done with English classes.

- gerunds / infinitives

- regular / irregular verbs

- count / noncount nouns

- transitive / intransitive verbs

- stative / nonstative verbs